Hush! Talk low! There are listening ears everywhere, Sam! I don't know why, but there is a chill at my heart, and I know my time has about run out. I've been on East with Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack, trying to show people what our plains life is. But I wasn't at home there. There were crowds on crowds that came to see us, and I couldn't stir on the streets of their big cities without having an army at my heels, and I got sick of it.

-Ned Buntline

Wild Bill’s Last Trail

The Illinois that James Butler Hickok was born into in May of 1837 was one of rampant lawlessness and vigilantism characterized by an informal group of outlaw gangs calling themselves the “Banditti of the Prairie.” The Banditti arose just as Hickok was born in the mid 1830s. Illinois Governor Thomas Ford would later write that Hickok’s birth county:

Was not destitute of its organized bands of rogues engaged in murders, robberies, horse stealing, and in making and passing counterfeit money. These rogues were scattered all over the north: but the most of them were located in the counties of Ogle, Winnebago, Lee and DeKalb. In the county of Ogle they were so numerous, strong, and organized that they could not be convicted for their crimes.

This area, known as the Rock River Valley, had seen a constant stream of immigrants arriving and seeking jobs after the state’s last Indian conflict, the Black Hawk War, had ended in 1832. Black Hawk, a member of the Sauk tribe, had crossed the Mississippi from Iowa with his “British Band” of Sauks, Kickapoos, and Meskwakis. Black Hawk’s group didn’t make any overtly aggressive movements, but US officials believed he planned to resettle some tribal lands that had been ceded to the federal government in the 1804 Treaty of St. Louis. Many settlers fled to Chicago, a small town that quickly bulged with both hungry refugees afraid of being attacked by natives as well as Potawatomi tribesmen who were increasingly worried they would be mistaken for hostiles.

In the brief series of conflicts that followed, the British Band were joined by a group of Ho-Chunk and Potawatomi warriors. Local Dakota and Menominee tribesmen sided with the US and against their long time foes. In the battles of Wisconsin Heights and Bad Axe, the US soldiers handily defeated Black Hawk’s hungry, tired, and depleted troops. Black Hawk himself escaped but was captured and imprisoned within a year.

The Black Hawk War was the deciding factor in determining the federal government’s policy towards the various native tribes in years to come. It also shaped the military views of two young soldiers who were on the same side of this conflict and on opposite sides of a later one, Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis. Davis was charged with escorting the captured Black Hawk back to Jefferson Barracks via steamboat. Lincoln was elected captain of his militia, later calling it, "a success which gave me more pleasure than any I have had since."

A drive through the Rock River Valley today affords views of many historical markers, commemorating pitched confrontations between the outlaw Banditti and their vigilante counterpart, the Regulators. One such marker points to the spot where “200 yards north of here, a granite boulder bears this inscription; ‘JOHN AND WILLIAM DRISCOLL were executed here June 29, 1841.’ These two men, father and son, were tried by 500 aroused citizens and then executed by a firing squad of one hundred eleven men. Doctors and scholars, ministers and deacons regarded this terrible example of lynch law as a public necessity.”

The Regulators were organized earlier that year after six Banditti outlaws who had been scheduled to stand trial escaped justice when their fellow Banditti burned down the New Oregon Courthouse on the day before the trial was scheduled. The Regulators suspected the so-called Driscoll Gang. Patriarch John Driscoll and one of his four sons, Taylor, had been convicted of arson in Ohio before emigrating to Illinois. When John Campbell rose as captain of the Regulators, John Driscoll sent him a letter offering to kill him. Campbell rejected this offer and made a counter proposal of killing Driscoll. Acting as postal service for his own letter, Campbell lead two hundred Regulators to Driscoll’s home.

It was in this atmosphere that James Butler Hickok was born on May 27, 1837. His father, a strong abolitionist, used their home in Homer, Illinois, as a station on the Underground Railroad. One of Wild Bill’s nephews, talking about the family home years later, would recall:

Grandfather built two cellars in his new home, one a false hidden cellar which was lined with hay. This was used as a station of the Underground. I lived in this house . . . and was not aware of this hidden cellar. It was brought to my attention by my father, who had me remove some boards in the living room floor and under this floor was a dry earthen room, probably six-foot square, and it was still lined with stems and traces of prairie hay.

William Alonzo Hickok died when his son was fifteen years old, leaving the younger Hickok mostly to his own devices. A fight with a sometimes friend named Charles Hudson ended in a canal, with both men believing they had murdered the other. To avoid the repercussions of the murder he assumed he had committed, James fled to Leavenworth in the Kansas Territory, where he found work as a stagecoach driver. At Leavenworth, Hickok joined the Jayhawkers, an abolitionist militant group that was willing to rob, fight, and kill to drive pro-slavery settlers out of Kansas.

In Kansas, Hickok laid claim to a 160-acre tract to farm and was elected constable in Monticello Township in 1858, his first experience as a lawman. The following year he found work with the Russell, Waddell, and Majors freight company. When this company started the Leavenworth and Pike’s Peak Express Company to deliver mail and news from St. Joseph, Missouri to Sacramento, Hickok was engaged as a wagon driver, and it was during his time with the company that he met the young Bill Cody when he saved the eleven-year-old from being beaten by some older men in a camp.

When Hickok was injured in an encounter with a cinnamon bear, the company sent him to their outpost at Rock Creek Station in Nebraska to recover while working some light duty in the station’s stables. The injured Hickok walked slowly and with a pronounced limp, his left arm damaged by the bear to point of being useless. In an event that has been much recorded and extremely exaggerated, Hickok, who had been left in charge of the station, went out to meet Dave McCanles, a local rough who had sold the property to the Express company and was angry about a late payment.

When McCanles, expecting to press the older and smaller station master for money was greeted at the door by the tall, quiet, and reserved Hickok, he demanded to see the other man.

“What in the hell, Hickok, have you got to do with this? My business is with Wellman, not you, and if you want to take a hand in it, come out here and we will settle it like men.”

Hickok stood for a moment before speaking, and then slowly replied,

“Perhaps ’tis, or ‘taint.”

Hickok stepped back inside to talk to Wellman when he saw McCanles move to raise a shotgun. Bill fired his own gun from inside the house, killing the man. In the subsequent moments, Hickok and the others at the station killed two more men who were with McCanles. A subsequent trial determined that Hickok was not guilty of murder based on self-defense, and Hickok left the state before friends of Dave McCanles could catch up to him. Versions of this story later appeared in newspapers and magazines after the Civil War, claiming that in the encounter Hickok had shot down a dozen members of the infamous M’Kandlas Gang. While all of the court documents refer to Hickok, whose given name was James, as William, they attach two other nicknames, Duck Bill or Dutch Bill. Some historians have theorized that he was called Duck Bill because of his thin lips. The nickname prompted Hickok to grow a mustache covering his mouth, but it wasn’t until after the war that Jim Hickok was known by only one moniker, Wild Bill.

During the Civil War, Hickok joined the Union initially as a scout and later as a wagon master in Sedalia, Missouri. When Confederate troops captured one of the wagon trains he was assigned to, he escaped to Independence, Missouri to rejoin his unit. While there, he chanced upon a saloon with a large crowd outside, and a mob that demanded the bartender’s blood. Hickok stepped in front of the saloon’s door and drew his twin pistols, demanding that the angry men walk away. When one of the men began to step forward, Hickok fired above his head, as well as the man standing next to him, the bullets passing close enough that both men could feel their hair move. Drawing back the hammers on his revolvers, Hickok had warned the crowd that he would shoot the first man to move forward. As the men dispersed a woman in the crowd had shouted, “My God, ain’t he wild!” and the name stuck.

Wild Bill continued to scout and was in the service of General Samuel R. Curtis during the Battle of Pea Ridge, where he was given the task of being a Union sharpshooter. From there he became a spy for the Union, detailing for the military commanders the movements of the Confederate troops in Missouri. After killing one cavalryman and two other rebels in a gunfight, he had taken the cavalryman’s horse and named her Black Nell. By the end of the war, he was employed as a member of the military police as well as a detective.

When the war ended, Wild Bill returned to Springfield. Also in the city was a man named Dave Tutt, who Hickok had encountered several times during the war. Initially, the two gamblers were friendly, but soon their relationship soured. Tutt may have started a relationship with a woman that Hickok had once courted. Hickok returned the favor by spending considerable time with one of Tutt’s sisters, prompting Dave to tell Wild Bill to leave her alone. There were rumors around Springfield that Tutt's sister was now pregnant with Hickok's illegitimate child.

Hickok refused to play cards with the man, so one night Tutt proceeded to fund every player that lost to Hickok, ensuring that they wouldn’t have to leave the table. Hickok again won, taking the money that Tutt had provided to keep the men in the game. Dave stood up to remind Wild Bill of a forty-dollar debt he owed on a horse trade. Hickok peeled the money from his winnings and handed it to Tutt. Tutt angrily continued that Hickok owed him thirty-five dollars more from a previous card game. Hickok said that he remembered that particular game’s debt being twenty-five dollars, and began to count out more bills.

Tutt reached for Bill’s Waltham repeater watch on the table and Hickok shot to his feet.

“I don’t want to make a row in this house,” spat Hickok to the other man. “It’s a decent house and I don’t want to injure the keeper. You’d better put that watch back on that table.”

Tutt laughed and walked out with Hickok’s watch. Taking the watch as collateral on the supposed $35 debt signaled that Tutt believed Hickok a man unable to pay his debts. To accept the insult would be to admit this as truth, which would have ruined Hickok as a gambler in Springfield, his sole source of income. Several days later, some friends of Tutt’s tried to cajole Bill into a fight, telling him that Tutt planned on wearing the watch when he crossed the town square the next day. Hickok told the men to warn Tutt that this was inadvisable, warning "He shouldn't come across that square unless dead men can walk." Hickok was in the square the next day when Tutt approached holding the watch. As he began to walk across the street, he pulled his pistol, and Hickok responded by drawing his pair and firing a shot from each simultaneously into Dave Tutt’s heart. Once again, a trial ensued and Hickok was found not guilty.

This gunfight was the source of the famous “shootout at high noon” trope that has pervaded western literature and drama ever since. There are conflicting accounts that state that Hickok had actually pawned the watch at Tutt’s saloon, but warned him not to wear it as he planned on returning to pay for it. Though Hickok had been cleared of murder by a jury, many citizens of Springfield remained convinced that he was a thug. When he was summoned to Fort Riley, Kansas for appointment as a deputy US marshal, he gladly accepted.

At Fort Riley, Hickok chased down and returned stolen government property, mainly horses, mules, and livestock. When General William Tecumseh Sherman arrived at the Fort headed to Omaha, a local doctor suggested that he take Hickok as a scout, as Wild Bill had proven himself as a tracker and marksman in his capacity as deputy marshal. After scouting with Sherman, he began to offer himself as a scout for civilian parties and would entertain them with stories and sharpshooting demonstrations.

When Hickok returned from one long excursion guiding a family to Fort Kearny, Hickok returned to Fort Riley to meet the commander of the new Seventh Cavalry Regiment that was then being formed, George Armstrong Custer. When Bill Cody came west after the failure of the hotel he had sought to establish in his own city of Rome, Kansas, he met Hickok again, and the older man suggested to the commanders at Fort Ellsworth (later Fort Harker) that Cody would be a good scout for the Fort.

By 1867, Hickok was in Hays City, the town that had overcome Cody’s Rome, as deputy US Marshal. His duties included apprehending horse thieves and arresting illegal timber cutters who made the mistake of harvesting wood from government land. These duties did not occupy enough of his time, however, to keep him from scouting for Custer’s Seventh Cavalry. In his book, My Life on the Plains, Custer described his former scout:

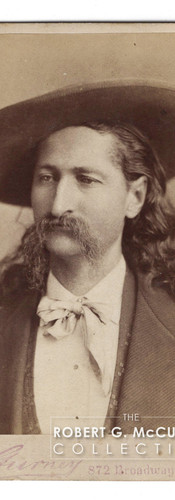

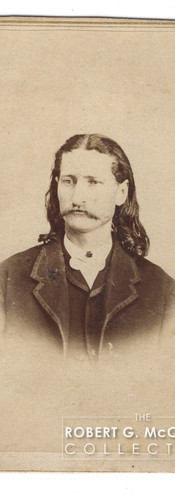

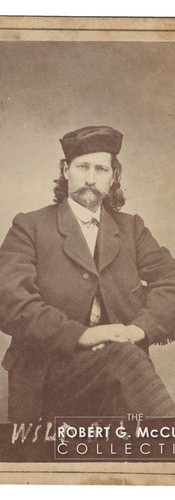

(He was) a strange character, just the one which a novelist might gloat over. He was a Plainsman in every sense of the word, yet unlike any other of his class. In person he was about six feet one in height, straight as the straightest of the warriors whose implacable foe he was; broad shoulders, well-formed chest and limbs, and a face strikingly handsome; a sharp, clear, blue eye, which stared you straight in the face when in conversation; a finely-shaped nose, inclined to be aquiline; a well-turned mouth, with lips only partially concealed by a handsome moustache. His hair and complexion were those of the perfect blond. The former was worn in uncut ringlets falling carelessly over his powerfully formed shoulders. Add to this figure a costume blending the immaculate neatness of the dandy with the extravagant taste and style of the frontiersman, and you have Wild Bill, then as now the most famous scout on the Plains. Whether on foot or on horseback, he was one of the most perfect types of physical man I ever saw. Of his courage there could be no question; it had been brought to the test on too many occasions to admit of a doubt. His skill in the use of the rifle and pistol was unerring; while his deportment was exactly the opposite of what might be expected from a man of his surroundings. It was entirely free from all bluster or bravado. He seldom spoke of himself unless requested to do so. His conversation, strange to say, never bordered either on the vulgar or blasphemous. His influence among the frontiersmen was unbounded, his word was law; and many are the personal quarrels and disturbances which he has checked among his comrades by his simple announcement that ‘this has gone far enough,’ if need lie followed by the ominous warning that when persisted in or renewed the quarreller ‘must settle it with me.’ Wild Bill is anything but a quarrelsome man; yet no one but himself can enumerate the many conflicts in which he has been engaged, and which have almost invariably resulted in the death of his adversary. I have a personal knowledge of at least half a dozen men whom he has at various times killed, one of these being at the time a member of my command. Others have been severely wounded, yet he always escapes unhurt. On the Plains every man openly carries his belt with its invariable appendages, knife and revolver, often two of the latter. Wild Bill always carried two handsome ivory-handled revolvers of the large size; he was never seen without them. Where this is the common custom, brawls or personal difficulties are seldom if ever settled by blows. The quarrel is not from a word to a blow, but from a word to the revolver, and he who can draw and fire first is the best man. No civil law reaches him; none is applied for. In fact there is no law recognized beyond the frontier but that of ‘might makes right.’ Should death result from the quarrel, as it usually does, no coroner's jury is impanelled to learn the cause of death, and the survivor is not arrested. But instead of these old-fashioned proceedings, a meeting of citizens takes place, the survivor is requested to be present when the circumstances of the homicide are inquired into, and the unfailing verdict of ‘Justifiable,’ ‘self-defense,’ etc., is pronounced, .and the law stands vindicated. That justice is often deprived to a victim there is not a doubt. Yet in all of the many affairs of this kind in which Wild Bill has performed a part, and which have come to my knowledge, there is not a single instance in which the verdict of twelve fair-minded men would not be pronounced in his favor. That the even tenor of his way continues to be disturbed by little events of this description may be inferred from an item which has been floating lately through the columns of the press, and which states that ‘the funeral of Jim Bludso, who was killed the other day by Wild Bill, took place today.’ It then adds: ‘The funeral expenses were borne by Wild Bill.’ What could be more thoughtful than this? Not only to send a fellow mortal out of the world, but to pay the expenses of the transit.

Custer’s wife Elizabeth Bacon Custer shared her husband’s assessment of Wild Bill, describing Hickok as a very modest man, free from swagger and bravado, and fast friends with her late husband:

Physically, he was a delight to look upon. Tall, lithe, and free in every motion, he rode and walked as if every muscle was perfection, and the careless swing of his of his body as he moved seemed perfectly in keeping with the man, the country, the time in which he lived…the frank, manly expression of his fearless eyes and his courteous manner gave one a feeling of confidence in his word and in his undaunted courage.

General Sherman had ordered Major General Winfield Scott to Kansas, to proceed into Indian Territory and try to convince the Cheyenne Dog Soldiers to make peace. The Cheyenne had signed a treaty agreeing to a reservation assignment in 1865, but the failure of the Senate to ratify the treaty meant that for the last several years the Cheyenne had not had a permanent home, and tensions had lead to occasional outbreaks of violence that had worried Washington. Far from assuring the Cheyenne that the white men wanted peace, the size of Hancock’s force had persuaded them that the army had come to start a war. When scouts told Hancock that the Cheyenne had abandoned their villages for fear of attack, he sent Custer and the cavalry after them. The frightened Cheyenne fled as quickly as they could, burning several white settlements as they passed, hoping to slow down the cavalry. Hancock ordered his soldiers to burn any Cheyenne villages they found.

Custer, believing that this policy was foolish and that Hancock had made a mistake in sending the mounted troops after the departing Indians, publicly made his views known, and was eventually placed in charge of the Smoky Hill Region of northern Kansas, tasked with restoring and protecting mail routes to and from Nebraska.

It was while scouting for Custer that Harper’s New Monthly Magazine published an article by George Ward Nichols that presented the stylized version of the encounters with Coe and Tutt that precipitated the Wild Bill legend that was accepted by the American people, if not the James Hickok that was known to his friends. Overnight, Hickok became a kind of frontier celebrity, and it was this celebrity and this article that would send Ned Buntline west to look for gunslingers and Indian fighters and buffalo hunters to fill his own works for Eastern audiences now clamoring for this kind of tale. Indeed, this story’s success lead directly to the publication of the dime novel Wild Bill, the Indian Slayer, the first of many fictionalized stories about Hickok.

Hickok spent much of 1868 again based in Hays, Kansas, where he gambled and joined up as a scout with the Tenth Cavalry at the fort where General Sheridan was now headquartered. Among Sheridan’s aides was Arthur MacArthur, father of the World War II General Douglas MacArthur. General MacArthur often told one of his father’s stories about Hickok to his men.

According to MacArthur, Hickok was serving as an interpreter between General Sheridan and the Sioux when Sheridan asked him to tell the Indians about the iron horse that was twice as fast as a horse and capable of carrying all the buffalo meat you could eat for a month. Hickok told the Indians, but they seemed unimpressed. Sheridan told Hickok to tell them about the steamboat that could move across the water without a sail or a paddle and could take the whole Sioux nation up the river. Again Hickok told the Indians and again they were unimpressed. “They don’t believe you, General,” Hickok told Sheridan. “Well then, tell them about the telegraph, and that with a little black box I can talk to the Great White Father in Washington and hear from him as well.” Hickok stared at the General for a few minutes before Sheridan said, “Bill! Tell them about the telegraph!” Wild Bill shook his head at the man and said, “General, now I don’t believe you!”

That winter, he was with Sheridan when the Tenth Cavalry joined Custer’s Seventh and General Carr’s Fifth Cavalries to seek out Tall Bull’s Cheyenne and Whistler’s Oglala Sioux. Bill Cody was head of scouts for General Carr, and the two friends were happy to see each other safe in camp. Working together as scouts for General Carr, the two Bills learned that a wagon was bringing beer from Fort Union to Fort Evans, and the two rode out and convinced the driver to sell them the beer, which they in turn sold to their fellow scouts.

Hickok was also happy to again see California Joe, who though he had been demoted from the position of chief of scouts for Custer because of his drunkenness, remained close friends with the General for the rest of his life. Joe fought in the Battle of the Washita with Custer, and Hickok was injured in a skirmish with Cheyenne warriors, one of whom managed to stab Wild Bill in the leg with a lance. Dragging himself back towards the fort, Hickok was found the next morning without a horse, using the lance that had stabbed him as a crutch to walk. Injured, Hickok returned home to recuperate and visit his ailing mother.

Quickly tiring of life in Homer, Illinois, Hickok returned to Hays, referred to by one newspaper reporter as “The Sodom of the Plains” because of its rampant lawlessness. Earlier lawmen in the area were killed, had disappeared, or left the office without warning. Full of freshly paid cowboys, buffalo hide hunters, soldiers from nearby Fort Hays, and professional gamblers, the city was a den of illegal activity, and the frightened citizens clamored for a sheriff. A fight between locals and colored troops from the Fort in May of 1869 lead to a petition to the Governor requesting a speedy appointment to the post.

It wasn’t until the end of August when J.B. Hickok was elected to the post. Though he had been a familiar sight in town as deputy U.S. marshal and Army scout, his new job afforded him a new level of respect in the city, and Hickok took advantage of this to ensure compliance with his word as sheriff. This respect gradually grew into constant tension for Wild Bill. Biographer Joseph G. Rosa wrote that:

It was in Hays that Wild Bill faced for the first time the reality of his reputation. At first mildly amused by the awed glances he received from all manner of people when he entered a town, room, train, or store, he was now forced to take the whole thing with deadly seriousness. No more was he just a “living legend”—he was a target of flesh and blood, a man with a reputation at the call of all comers who thought they could take it.

Indeed, within a few days of assuming the position, Hickok had shot a killed a man who drew his gun when Bill approached him to enforce an anti-firearm notice posted in town.

Hickok earned the respect of the citizens of Hays, willing to arrest lawbreakers that other lawmen feared. In addition to lawlessness by the citizens of and visitors to the city, Hickok was occasionally charged with arresting and returning deserting soldiers from the nearby Fort. In late September Hickok was involved in a conflict with a man named Sam Strawhun, who Wild Bill dealt with some time before when he tied the drunk Strawhun and some of his friends to fence posts to allow them to cool off after a long night of drinking and fighting. Strawhun had more recently been involved with the murder of a postal clerk but managed to escape town before justice caught up with him.

On September 27, 1869, some months after he had met Texas Jack and advised him to make for Nebraska, Wild Bill was alerted that Strawhun and his companions were clearing out a local saloon. Strawhun’s gang had each ordered a beer and then taken the glasses out of the saloon and into a vacant lot before returning to order another round, quickly leaving the bartender without a glass for the beer the men still clamored for. When Strawhun threatened to kill someone “just for the luck,” the beleaguered barkeep had called the law. Wild Bill visited the vacant lot to retrieve the empty mugs before walking into the building and began depositing the beer glasses on the bar. With a glass in each hand, Hickok reproached the group.

“Boys, you hadn’t ought to treat a poor old man this way.”

When Strawhun threatened to shoot anyone who interfered with his fun, Hickok slowly set the remaining glasses on the bar. Strawhun reached for one of the glasses and made as if to throw it at Hickok, who sent a bullet between the man’s eyes. A formal review of the event by a jury found that Hickok had acted in self-defense.

By January of 1870, Hickok’s term as sheriff was up, but he remained in Hays until July, when he was jumped at a local saloon by a group of five soldiers. Managing to shoot two of the men, Hickok escaped the rest of the group and left Hays, heading for Topeka. He spent the winter and spring gambling and drinking, but otherwise keeping his head low. In early April of 1871, Wild Bill was offered a position as marshal of Abilene. The town’s mayor was Joseph McCoy, the man who had built the stockyard and turned Abilene into the cow capital of the west. He wrote of making the choice for marshal, “For my preserver of the Peace, I had ‘Wild Bill’ Hickok, and he was the squarest man I ever saw. He broke up all unfair gambling, made professional gamblers move their tables into the light, and when they became drunk stopped the game.”

After his fight with Phil Coe and the accidental shooting of Deputy Mike Williams, the Texas cowboys now afraid of the consequences of bad behavior and the citizens of Abilene, weary of the gamblers, prostitutes, and rowdies that descended on their town each year determined to seek out another destination for their herds. Newton, Wichita, and Dodge City all became king of the cowtowns, and Wild Bill walked away from law enforcement in Kansas. He participated in Colonel Barnett’s buffalo hunt in Niagara and then went to Boston. He traveled to Colorado to visit Charlie Utter, a friend from his days in Hays. He traveled to Kansas City where he spent time as a professional gambler. He was at the Kansas City Fair along with thirty-thousand other visitors when a number of men from Texas asked the band to play Dixie. When some locals protested, the Texans took out their revolvers. Hickok stepped forward and stopped the music, to the anger of the Texans. Despite the overwhelming numbers, none of the men were willing to fire at Wild Bill.

An article in several newspapers throughout the country reported that Hickok had been shot and killed, perhaps by a friend or relative of Phil Coe. One paper reported that he William Hickok had been corralled by Texans he had angered during his time as marshal of Abilene. Growing tired of reading of his demise, Hickok wrote to the St. Louis Missouri Democrat:

To the Editor of the Democrat,

Wishing to correct an error in your paper of the 12th, I will state that no Texan has, nor ever will “corral William.” I wish you to correct your statement, on account of my people.

Yours as ever,

J.B. Hickok

Wild Bill

In a second letter, sent to the same newspaper on March 26th, 1873, Hickok wrote that “Ned Buntline of the New York Weekly has been trying to murder me with his pen for years; having failed he is now, so I am told, trying to have it done by some Texans, but he has signally failed so far.” With Buntline no longer a factor in joining Cody and Omohundro in their stage venture, and a lack of prospects on the western plains, Hickok agreed to give acting a shot. That fall, Wild Bill Hickok stepped off the train in New York City to join his old friends Buffalo Bill Cody and Texas Jack Omohundro in a new play, The Scouts of the Plains.

Comments